Knee Problems in Dogs

Your dog’s knee joint (or stifle) is a precisely engineered hinge at the meeting point between the femur (thigh bone), and the tibia (shin bone). When your dog wants to extend his knee, he engages his quadriceps muscle. When he wants to flex his knee, he relaxes his quads and engages his hamstrings.

Unlike humans, a dog’s knee is designed to be bent when resting or standing still. And it is only supposed to be able to bend in one plane. It shouldn’t be able to bend sideways, swivel, slide, or hyperextend. Important features of the knee joint, including the patella (kneecap), cruciate ligaments, and collateral ligaments, work together to keep all movements restricted to the intended range of motion: on track, and in one plane.

Any problem affecting one part of the knee mechanism can impact the function and health of the whole knee. Things that can harm the knee include inherited or developmental malformations, degenerations, inflammation, and injuries.

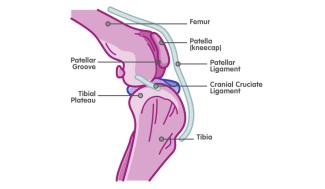

Knee anatomy:

Let’s look at some of the important parts of the knee joint, and what they do:

The femur is also known as the thigh bone. It runs from the hip down to the knee. The femur has a typical “doggy bone” shape at its lower end, where it meets the knee joint. The groove in between the two knobs on the end is called the patellar groove.

The tibia is also known as the shin bone in humans. It runs from the knee joint down to the tarsus, or ankle.

At the knee, the femur sits on top of a slanted shelf on the tibia called the tibial plateau.

The patella, or kneecap, is a bone that sits in front of the femur at the knee joint. It fits perfectly into the patellar groove. The patella is encased within a thick strap of connective tissue called the patellar ligament. The patellar ligament is what connects the powerful quadriceps muscle to the tibia. When the quadriceps muscle is engaged, it pulls on the patellar ligament and extends the knee joint. The patella slides up and down within the patellar groove, keeping the motion of the knee within one plane.

Because the femur sits on the slanted tibial plateau, whenever a dog puts weight on his leg, the femur wants to slide backwards, off the back of the tibia. The cranial cruciate ligament acts as a tether between the end of the femur and the top of the tibia. It prevents this sliding motion.

The collateral ligaments of the knee work together with the patella to prevent the joint from bending sideways or swiveling inwards and outwards.

Some common knee problems:

Two of the most common illnesses affecting the knees of dogs are patellar luxation and cruciate ligament disease. Sometimes these conditions even happen together. Let’s take a close look at each:

Patellar luxation:

Sometimes called loose kneecaps, patellar luxation happens when the patella comes out of the patellar groove on the front of the femur. Most patellar luxation is an inherited abnormality. This means that the shape of the dog’s bones, and particularly the depth and shape of the patellar groove, does not keep the patella in place. The patella can luxate either medially or laterally to the patellar groove. Less commonly, trauma can also cause luxation of the patella.

Some patellae just come out of the patellar groove occasionally, while others are permanently out of place. When the patella is luxated, your dog can’t bend his knee normally. In addition, the knee joint loses alignment and stability. This allows some swivel movement between the femur and tibia. Over time, instability causes arthritis, pain, and inflammation. It also puts stress on the cruciate and collateral ligaments.

Early on, a dog with patellar luxation may occasionally hold up one hind leg or skip a step. Over time, lameness or limping may become more persistent, and the dog may develop a bow-legged or knock-kneed appearance.

Patellar luxation is one of the most common orthopedic conditions in dogs. The inherited form of patellar luxation occurs most often in small breed dogs, but there has been an increased incidence of the illness observed in large breed dogs in recent years.

Cruciate ligament disease or rupture:

As mentioned, the cranial cruciate ligament serves as the tether that prevents the femur from slipping down the slope of the tibial plateau. Whenever a dog is standing, this tether is bearing a load. Due to conformation, inflammation, hormones, and other factors, the cruciate ligament can degenerate over time. The diseased ligament slowly loses strength, like a fraying rope. When the ligament is fragile in this way, natural stresses like running, jumping, playing, navigating uneven terrain, or minor trips and falls can cause a partial or complete rupture.

A dog with cruciate ligament disease may be completely asymptomatic or may limp intermittently as the degeneration occurs. When the ligament is ruptured, a dog will feel the uncomfortable slipping motion every time he puts weight on his back leg. Most owners will notice that their dog has suddenly become lame on one of his hind limbs, usually after an ordinary activity. Dogs may also resist activities that demand more back-end power, like climbing stairs or jumping.

Diagnosis:

Your veterinarian will start to form your pet’s diagnosis by listening to your past observations about your pet’s activity, behaviours, and lameness history. She will observe your dog’s gait and examine all joints of the affected limb carefully. She’ll take note of any pain, swelling, changes in range of motion, and cracking or popping sounds.

Typically, sedation is required to test the joints for instability and take good quality radiographs. Sometimes, advanced diagnostics like MRI or arthroscopy are also used to visualize the knee joint.

Treatment:

Depending on the size, age, and health of your dog, different treatment options will be available. Conservative management like pain control, physical therapy, and braces may be offered to smaller patients, patients with minor knee changes, or patients with health issues that contraindicate surgery.

Surgical management to improve stability in the knee is considered the best option for healthy patients. It is particularly important for treating larger dogs, dogs with severe knee abnormalities, and those with problems in both knees. For both patellar luxation and cruciate ligament disease, the goal of surgery is to re-engineer the joint for improved stability and get the patient walking comfortably again. Several surgical techniques are available to reduce luxation, slipping, swiveling, and other forms of instability.

Surgery is often combined with rehabilitative therapies and alternative medicine techniques.

Prognosis:

More than half of dogs with patellar or cruciate ligament problems on one side will have or develop the same condition on the opposite side.

After treatment, the prognosis is excellent for improved comfort and mobility for both patellar luxation and cruciate ligament disease.

Because of the history of joint instability, it should be expected that all patients will experience some level of arthritis, particularly as they age. Veterinarians can help pet owners manage their pets’ arthritis with a combination of medication, weight management, nutraceuticals, and physical therapy.